Minority Report (2002)

Rated PG-13

(for violence, language, some sexuality and drug content)

Released: June 21, 2002

Runtime: 145 minutes

Director: Steven Spielberg

Starring: Tom Cruise, Samantha Morton, Max von Sydow, Colin Farrell, Lois Smith, Tim Blake Nelson, Kathryn Morris, Neal McDonough, Steve Harris

Available to rent through Amazon Video.

Day 22 of “30 Days of Spielberg”

Ready to amp up the action without diminishing the philosophical debates, Minority Report finds Steven Spielberg in a strong Kubrick afterglow following A.I.: Artificial Intelligence. His second sci-fi film in a row, Spielberg dives into a nearer future – the year 2054 – in the closest thing to Blade Runner he’s likely to make (which is fitting since this, like that Harrison Ford classic, is based on a Philip K. Dick short story).

Minority Report is sci-fi noir with heavy doses of Hitchcock and even weird splashes of David Lynch, and it’s the most straight-up suspense thriller for Spielberg since Jaws. It’s also a murder mystery mixed with a Fugitive-like “man on the run” hero trying to prove his innocence. And while not a 9/11 parable in any way, the film’s core themes broach that tragic event’s first major ripple effect: pre-emptive strikes. At 2 ½ hours, Minority Report is a movie that never drags because it’s packed with so much – action, style, and brains, plus Tom Cruise flexing both muscles and range – that’s firing on all cylinders, and fueled by some really spectacular set pieces. Dadgum, this is a helluva movie.

It’s the mid-21st Century, and for six years in Washington D.C. there hasn’t been one murder. That’s all thanks to their Department of PreCrime, a branch of the police force that has developed a system to predict murders before they actually happen. Law enforcement stops the lethal crimes before anyone is harmed, yet would-be killers are still arrested and imprisoned. With a staggering success rate of 100% for over a half-decade, PreCrime is now on the verge of going national.

The system has been developed both operationally and legally. It’s fascinating to see how it works, particularly as it involves a check-and-balance with a live patch-in by two judges from the judicial branch. The chief law enforcement officer – Captain John Anderton (Tom Cruise) – processes and prosecutes every arrest with their oversight. This has been seriously thought through to fit within a Constitutional system, force accountability, and avoid Orwellian overreach.

But of course, the system has a dark side. There’s the most obvious issue: arresting and sentencing people based on a prediction of their actions and not actual murders (a thorny ethical dilemma that the film actually does a credible job of arguing in favor of). Then there’s the source of the predictions themselves: three humans (twin males and a woman) that, by virtue of a scientific experiment that went awry, have extra sensory psychic powers.

When joined in PreCrime’s technology, these PreCogs (short for Pre-Cognitives) are able to see murders in detail before they happen, most often days in advance. (The PreCogs can’t see other crimes, like rape, because those acts – while brutal – don’t reach the ultimate breach of life that serves as the trigger for these visions.) That’s a lot of setup, yet Spielberg dispenses it all with fascinating, entertaining clarity.

But here’s the real hook: what happens when the chief officer who’s made every PreCrime arrest (Cruise’s aforementioned Capt. Anderton) pops up as the killer in one of the PreCogs’ visions? Killing a guy, no less, that Anderton’s never even met. It’s riveting to watch it all unfold, particularly as it builds toward the seemingly inevitable murder (which goes down at the peak of the film’s second – not final – act, spiraling the story in a new, more complicated direction for the last third).

Suffice it to say, there’s not merely a bug in the system; someone’s actually rigged it (impossible as that seems) and Anderton’s been set up. It’s up to him to figure it all out while being hunted down by police and federal agents, for a murder that he hopefully won’t commit.

The moral dilemma works on several levels. First, on the face of the premise, it may seem there’s not much to debate; we shouldn’t arrest people for murders they haven’t committed, plain and simple. It’s wrong. But that 100% drop in murders is hard to argue with, and it raises a counter moral argument: if we can eliminate murders with absolute certainty, don’t we then have a moral obligation to implement the very system that achieves it? This becomes particularly convincing as would-be murders have been reduced to crimes of passion; people have come to realize the futility of pre-meditation.

Then there’s the PreCogs themselves. In order to be operational, they’re forever quarantined, unable to live anything close to resembling normal lives. Compounding this inhumanity is the fact that, by the very nature of what they foresee, they’re psychologically and spiritually burdened with the intensity of every murder they predict because they’re experiencing it as well. It’s tantamount to cruel and unusual punishment, an altruistic torture. (As Anderton says at one point, “You can’t think of them as human.”) If such a system were even possible, it’d be hard to stomach what those PreCogs are put through, even with a 100% success rate.

In short, the core ethical debate becomes one simple but very hard to answer moral question: Utopia, but at what cost?

Anderton is a complicated character in his own right. A hero and crusader to the masses, he struggles with a secret drug addiction, one he’s battled since the kidnapping and loss of his son. That tragic event led him to lead the PreCrime initiative, but it’s also torn him apart as well as his marriage, leaving him to ease the pain by scoring narcotic hits. He’s faithfully held a moral integrity on the job, but his tormented soul does make you wonder: is he capable of murder?

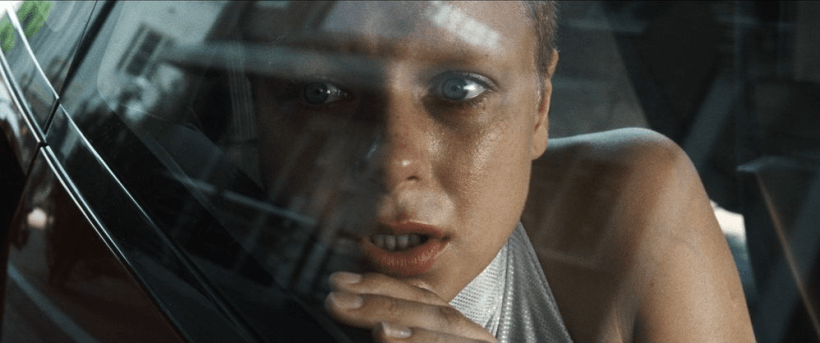

While the surface setting is clearly sci-fi, the dark and seedy core of Minority Report is Film Noir through and through (making for Spielberg’s edgiest effort, complete with illegal drugs, some gruesome violence, and occasional sexual proclivities in various corners of the city’s underbelly). Anderton is the classic morally compromised gumshoe, he’s seemingly framed by a mysterious perpetrator that may have roots in a government conspiracy, and Agatha – the female PreCog – puts a tragic, mesmerizing spin on the femme fatale. It’s a heartbreaking turn by Samantha Morton in a criminally under-recognized performance that must’ve been absolutely exhausting to undertake – physically, mentally, and emotionally.

For Cruise’s part, it’s one of his all-time best (and also criminally ignored). A wide range of scenarios require just the right level of nuance to be made credible. The would-be murder, in particular, has Cruise running an emotional and moral gamut. I can’t account for his controversial personal life, but on-screen the man can flat out act with the best of them.

The rest of the cast is pitch-perfect, including Colin Farrell and Max von Sydow, but a particular highlight is character actress Lois Smith. Her one scene, right at the film’s halfway mark, is crucial to the plot, and unforgettable because of what she does with it. Smith plays the co-inventor of PreCrime (now retired), a sweet grandmother type with an eerie, possibly deviant edge. Anderton goes to her for clues and possible answers.

During the course of their meeting, she unpacks vital backstory before revealing a possible loophole (the titular “minority report”). Smith delivers it with a strange, hypnotic charisma, and caps the whole scene with a, um, “goodbye” that you’d never see coming (Anderton sure doesn’t).

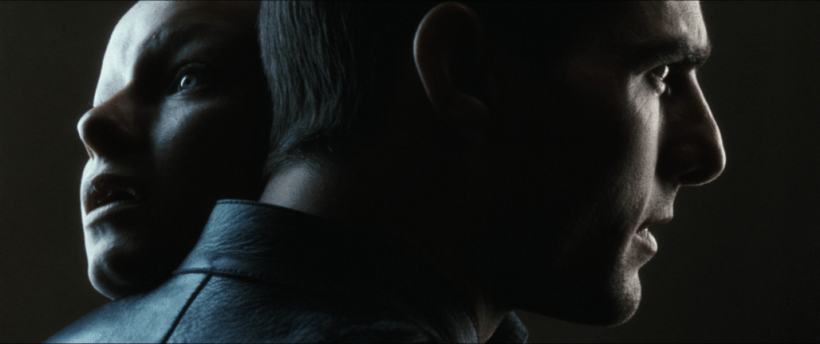

Minority Report is also a standout effort by Spielberg’s perennial cinematographer Janusz Kaminski. He creates a visual texture that places the sleek, clean, highly advanced area of D.C. in the same world as the dark, dank, and sleazy corners. And the climatic standoff (there’s always one in a noir) is shot and framed like something straight out of the 30s or 40s, with stark lights and shadow that, at times, form art deco patterns. He also strikes artful compositions, most notably the symbiotic placement of John and Agatha’s heads during an embrace, in close-up. The symmetry is beautiful and, with the emotion of the moment, breathtaking.

Kaminski also reels off a few patented Spielberg Oners, most notably an overhead see-through tracking shot of an entire apartment complex that involves the choreography of action, effects, and precise timing. But there are several other Oners more subtly staged, too, like an early elevator confrontation between Cruise’s Anderton and Farrell’s federal agent.

Oh, and Spielberg throws in some pointed satire about advertising saturation, too, something he (and his team of futurists) had forecast for 2054 but is already beginning to look familiar in 2016.

The final climactic turn does revolve on an errant slip of the tongue, something perhaps a bit too convenient for a plot so perfectly constructed and flawlessly dense, but it’s a forgivable choice as it’s not only a classic genre staple but also expedites the inevitable. By the time it happens we know where this is going (and we’re supposed to, it’s all part of how Spielberg ratchets the suspense), so laboring the reveal even more would’ve be counter-productive.

Despite its financial and critical success, Minority Report sort of remains one of Spielberg’s hidden gems. It has the intelligence, style, intensity, and whirlwind of emotional pathos (from Anderton’s arc to Agatha’s tormented soul) that more summer movies should aspire to, plus it confronts still-relevant issues (back in 2002, it tackled the notion of “pre-emption” just as the Bush administration was preparing to invade Iraq as a preventative measure against what Saddam Hussein may have done in a post-9/11 world).

So before you plop down money for an obligatory Transformers sequel (or other money grabs of its ilk) – the kind you’re already complaining about before you’ve even stepped foot in the theater – stop! And rent Minority Report instead.

Available to rent through Amazon Video.

NOTABLE TRIVIA

- This was Spielberg’s first film (other than the Indiana Jones movies) since 1941 to be shot in the wider-screen 2:35:1 aspect ratio. Starting with E.T., Spielberg shot his films in the more-regularly shaped rectangle aspect ratio of 1:89:1 (the same frame size as modern-day HDTVs). No specific reason for this differential is known, but the shift to 1:89:1 back in the 80s was likely due to the advent of home video and “pan-and-scan” visual cropping. By shooting in 1:89:1, less of the original image needed to be cropped out.

- The “PreCogs” were all named after famous mystery writers. Dashiell Hammett, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Agatha Christie.

- Three years before filming began, Spielberg assembled a team of 16 future experts to brainstorm what technology would look like in all aspects of modern society in the year 2054.

- The car factory action sequence is based on an idea that Alfred Hitchcock had for North By Northwest but had been unable to shoot.

- The short story on which this is based was almost initially produced as a sequel to Arnold Schwarzenegger‘s Total Recall, with the setting moved to Mars.

- In Philip K. Dick’s original short story, John Anderton is short, fat, and balding.

- Spielberg’s version was almost filmed right after Saving Private Ryan. Spielberg decided to put the script back into rewrites, but not before having decided to cast Cate Blanchett as Agatha, Matt Damon in Colin Farrell’s role of Witwer, and Ian McKellen instead of Max von Sydow.

- Cruise’s Vanilla Sky director Cameron Crowe makes a cameo appearance as a train passenger reading a newspaper. Vanilla Sky co-star Cameron Diaz sits behind him.

- This was Spielberg’s first film for 20th Century Fox.

- The film’s title doesn’t appear on-screen until the end credit roll.

I think I enjoy your trivia as much as the reviews. Definitely one of Spielberg’s under-appreciated film, and the last one he made that I unequivocally liked. Too bad Cruise became his foil for a bit there, as I agree that this was head and shoulders above his normal performance.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, opinions are definitely mixed on Cruise’s acting ability (even before his 2005 Crazy Train spell). For me, though, I’ve not only always had great respect for him as an actor but generally feel he’s really underrated. So performances like this one don’t surprise me; they just confirm what I already feel about his level of talent and range.

LikeLike

Afraid I can’t agree about the plot being “perfectly constructed”. The first-act exposition establishes the rules of the game and then the rest of the movie utterly ignores them.

Supposedly, the whole pre-cog thing works on the principle that if you see something is about to happen, you can act to prevent it. The act of seeing a future murder creates a ripple effect (or butterfly effect) that can prevent the murder from happening if the ripples (the cops, etc.) get there in time.

By that logic, John Anderton’s future murder should have been undone the moment Anderton *saw* it. The ripple effect had very little distance to travel, because the supposed murderer was *right there*. But instead, the film tells us that seeing the future murder *caused* the murder to (almost) happen.

And then there’s the question of how someone could *conspire* to make the future murder happen. If the pre-cogs are simply seeing the natural end result of cause-and-effect (that is, the result that would have happened before the pre-cogs started the ripple effect), then how would someone set up a murder that could only happen *as a result of* the ripple effect? Supposedly, the conspirator told a man to put a bunch of photos on a bed somewhere. How does *that* trigger the pre-cogs, if Anderton was never going to be in the bedroom without the pre-cogs setting in motion a chain of events that put him there?

There’s some beautiful futurism and/or social satire here, though.

LikeLike

I definitely see the whole construct differently than you do, in large part because I don’t think it all must somehow follow a particular logic as you laid out (or as anyone might lay out). You say “by that logic” as if it’s the only possible ripple effect, when the whole point of the movie is the concept of the “minority report”, i.e. infinite possibilities.

But even the minority report concept aside, fundamentally, I don’t agree that there is only one mathematical cause-and-effect equation once a particular bit of knowledge is gained. More philosophically, another layer of the whole movie is this idea of Pre-Destination vs. Choice which is being explored; are certain things destined regardless of what we do or don’t do?

Then beyond THAT, I think the simple metaphor Anderton demonstrates to Weitwer with the rolling ball serves this question well. Basically, the ball is going to roll and it is going to fall, and PreCrime is simply the hand that “catches” and stops a murder before it drops.

Yes, it’s a bit more complicated when it’s Anderton viewing himself as the culprit (a luxury all other murders don’t have, particularly since they’re not even planning on murdering because these are crimes of passion; pre-meditation has been eliminated in this PreCog world). Even so, I don’t think the only line of possible logic is that seeing the future murder *caused* the murder.

Basically, you’re restricting cause-and-effect to a linear time frame. The metaphysical pre-cognitions, by their nature, transcend linear time, they’re above and outside of normal time and space, so to keep logic within time and space is too reductionist, I think. The PreCogs have a God-like power (another theme/idea of the movie), and so the “logic” of that kind of power can’t be confirmed or disproven by linear logic.

Shoot, even in our linear world, the results of our actions often aren’t what we intend. The movie is challenging our whole notion “control”.

LikeLike

Actually, it is *precisely* the rolling-ball metaphor that the movie betrays by saying that the pre-cogs can actually *cause* what they predict, and that regular people can somehow (though it is never explained how) cause the pre-cogs to set in motion the chain of events that results in what they predict.

When Anderton sees himself committing the murder, he is the ball *and* the hand. That’s complicated enough. But then the movie adds this extra layer of complication by saying that a third party (a non-transcendent party!) did something that caused the hand to *roll* the ball instead of catching it.

The “minority report” concept, as I understand it, merely relates to the multiple possible futures that the pre-cogs see. It refers to the way our possible futures branch off from our one-and-only present. (Time is linear in the past and present, yes. The future is non-linear only because it hasn’t happened yet.) The “minority report” concept has no bearing on the mechanics of cause-and-effect themselves.

LikeLike

SPOILER ALERT POST:

Right, I agree that the “minority report” concept has no bearing on the mechanics of cause-and-effect themselves, but it does reveal that the mechanics don’t always follow predictable, controllable, or assured cause-and-effects. There’s more than one possibility – or, more to the point, we can’t necessarily control possibilities, even with knowledge, or self-knowledge. We *may* be able to control, but it’s not a guaranteed outcome even when we’re conscious of it

Also, the movie isn’t saying or suggesting that pre-cogs can actually cause what they predict, but simply that *the human operators* (i.e. Anderton) who view their visions can be tricked through how the pre-cogs operate.

Regular people aren’t causing the pre-cogs to do anything or set anything in motion. SPOILER ALERT They are committing murders by replicating past ones (which can be viewed on file) so that the humans (Andertons) who view those replicated murders think they’re seeing a repeating glitch and not a new murder. The pre-cogs just do their thing, and the non-transcendent party simply sends the pre-cogs an image that they know the human observers will dismiss. The non-transcendent party has figured out a way to trick the other non-transcendent party, but the pre-cogs themselves aren’t being tricked and controlled. They’re just an image delivery device.

Now as it relates to Anderton being the ball and the hand. I’d have to go back and rewatch exactly how things go down, but my perception is that the non-transcendent party is setting the ball (Anderton) in motion, not Anderton himself.

I’m not saying there isn’t a paradox at work here, there is, but it’s god-like and working outside space and time (like, say, The Holy Trinity does) and so I don’t think we can confine it to space and time.

In addition (and most importantly, I believe), the movie isn’t using that paradox to explain new levels of science or metaphysics but simply – through science FICTION – to explore ethical and moral questions. I don’t believe the film is required to explain or validate its paradox (I mean, there’s so much here that’s asking us to suspend disbelief, starting with PreCogs even being possible). The paradox is simply being used here, in fiction, to ask and ponder a What If?

LikeLike

Oh, I wasn’t even thinking about the replicated murder(s). I was referring only to the person that Anderton sees himself murdering.

Anderton ends up meeting that person *because* he saw himself murdering that person, which gets the whole cause-and-effect things backwards. If Anderton had not seen himself murdering that person, he would never have run away from his colleagues and into the situation where he ends up (almost) murdering that person. *That’s* what I mean when I say that the pre-cogs caused what they predicted.

So the question is how the non-transcendent party tricked the pre-cogs into showing Anderton something that Anderton would never have done if the pre-cogs hadn’t shown it to him. As far as we know, the non-transcendent party simply told a man to put some photos on a bed somewhere at a certain point in the future — but surely *that* wouldn’t have been enough to trigger the pre-cogs?

To put this another way: the non-transcendent party’s plot hinges *entirely* on the predictability of cause-and-effect. He could only have planned all this if he had known that seeing the future *causes* it rather than *prevents* it. But that, according to Anderton’s opening speech, is not how this is supposed to work.

LikeLike

MORE SPOILERS:

Ah, okay, sorry, I see what you’re saying now.

I don’t know if this will suffice for you, but according to Scott Frank, the screenwriter, the PreCogs aren’t necessarily seeing/predicting set events (aka the Minority Report possibilities), and therefore things don’t entirely hinge o the predictability of cause-and-effect.

Sometimes the future is set (and so no MRs), sometimes it’s not (MRs). Either way, the future event doesn’t need to “be staged” or predictable, it needs simply to be set in motion. Once you set events in motion that could lead to a murder, the PreCogs will pick up that possibility. And so, by simply hiring this man to pose as Leo Crow, Burgess has set events in motion. Once those events were set in motion, they created the possibility of what the PreCogs forecast.

Here’s a quote from Scott Frank:

“Burgess knew that the only person Anderton would, without hesitation, want to kill would be the man Anderton believed had taken his son. Therefore, all Burgess had to do was ‘hire’ Leo Crow — a lowlife child molester already in prison — to pretend to be this man with the promise of paying his family a large sum of money in return. In the backstory, Burgess would then start to arrange how Anderton might come into contact with him. But he doesn’t even have to go that far, because once Burgess starts his plan in motion, the precogs will immediately see the END result — the precogs will pick up that Anderton will confront the man who took his son and kill him. It plays out differently in the actual room because Anderton, unlike the people he’s arrested the past six years, has actually seen his own future. So he can change it. And he does. Or tries to.”

In other words (I think), Burgess was pre-meditating Anderton’s act of murder for him.

One additional thought: theoretically, Burgess could have made previous attempts to set things in motion that didn’t lead to a possibility of murder that PreCogs would foresee (there may have been some trial and error involved), but he eventually landed on an attempt that did.

LikeLike

That’s an interesting quote from Scott Frank, but I don’t think I buy it. Whatever method Burgess might have had in mind to put Anderton in contact with Crow, it is highly *highly* unlikely that it would have led to the exact same moment, in the exact same room, with everyone standing in the exact same position as what the pre-cogs saw. From the moment Anderton witnessed himself committing the murder, the future should have started changing, but that’s not what the movie shows us.

LikeLike

But that’s the thing: Burgess and Crow never staged anything, so nothing was replicated exactly. All Burgess had to do is set things in motion by renting the room, hiring “Crow”, and telling Crow what he wanted to have happen. It just so happened that he was able to set the *right* actions in motion to create that possible outcome, and that possible outcome is what the PreCogs saw, not anything that was ever staged. It was pre-meditated, sure, but the plan itself was enough – just like the plan itself would’ve been enough in *any* case of pre-meditated murder that the PreCogs would see a future vision of.

As far as things needing to have started to change once Anderton saw the future, I don’t get why you think that’s an absolute must. Sure, they could, but why would they necessarily need to? Also, there is the whole philosophical notion of self-fulfilling prophesies. In this case, to solve the mystery, the best possible way to do that was to go to the scene of the crime, at the time of the crime, so it was self-fulfilling by Anderton’s own intention.

Even so, the future actually does change. When Anderton’s watch strikes zero, he still hasn’t shot Crow yet (despite there not having even been a minority report for this incident). Anderton instead tries to arrest him. Then Crow commits suicide by violently forcing Anderton to shoot him, making it look similar to the PreCog vision. But again, the future did change.

LikeLike

It has been a long time since I saw the film, but my recollection is that various details in the pre-cogs’ vision came true *exactly* as Anderton arrived at the moment of decision, so the replication was pretty precise. It was, indeed, the replication of all these elements that made the temptation to go through with the murder all the more potent, as I recall; it seemed to have been predestined, so who was Anderton to stand in the way of fate?

As for things changing the moment Anderton saw the future: See what I said above about the “ripple effect” that flows out from the pre-cogs towards the future crimes that they see. In Anderton’s case, the ripples didn’t have far to travel at all, and once he became *aware* of that possible future (a future that supposedly would have happened if the pre-cogs and the people using them had not become aware of it), the mere fact of his awareness would have changed his actions and all the other actions that followed.

As for self-fulfilling prophecies… well, the whole *point* of the pre-cogs is that their visions *prevent* the things they saw from coming true (except in cases where the visions arrive too late for the “ripple effect” to reach the scene of the crime before it happens).

But I’m not sure we should expect philosophical coherence from Spielberg. I still have weird memories of a bonus feature on the A.I. Artificial Intelligence DVD where Spielberg tried to say something profound about being attached to a toothbrush, or something like that, and it made no sense at all.

LikeLike